Crazy Books, Continued

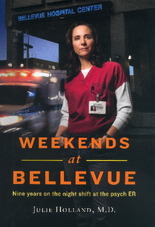

/One of the wonderful (and possibly self-fulfilling or even egotistical) aspects of blogging about books is that some of their authors are alive, a smaller percentage of those authors are on social media, and an even smaller number of them actually respond when mentioned in a tweet. Well, lucky me, that happened! In my post earlier this week on books related to mental health, I mentioned two of Dr. Julie Holland's books. I included her twitter handle in my tweet about the post, and she favorited it. I have no idea if she read it, but I still feel like that is pretty nifty.

So that makes me hesitant to mention some of the drawbacks to her earlier book. (What if she is actually reading this? Does that make her cool and in tune with her readers? Or overly concerned about public opinion? Or does that just make me seem paranoid?) Anyway, I feel like I need to qualify my earlier praise of Weekends at Bellevue. At some points, I was appalled by her hastiness and tough-guy attitude toward her patients. To be fair, she realizes that this attitude is problematic and off-putting to some, and she does work to change it. Nevertheless, it's concerning to see a physician relate patient stories in such a callous tone. Here's an example:

“After I spoke with the hand surgeon and got him to agree to come down, the patient changed his mind, and decided he didn’t want anyone to touch his hand. I got really pissed off then. I argued with him for a while and got nowhere, and then I called him a pussy ... “You’re just chickenshit to have the surgeons sew your hand.” I ridiculously believed I could double-dog dare him into having sutures. He was handcuffed to the chair.”

It's admirable that she allows herself to be this vulnerable, on the one hand; though on the other, it's disarming and worrisome to see a doctor--a psychiatrist no less--not only think, but also express, such contempt for a patient. She writes more about her "need for self control" with her therapist, Mary.

Medical school seems to be part of the problem, as she discusses early in the book: "Everywhere, instead of people, I learned to see pathology. I was learning to think like a doctor" (25). I want my doctors to see me as a person! To see only my pathology is to see only a small piece of who I am, and it may even mean missing out on key information that could lead to a diagnosis.

Her softer side emerges at times. She conveys her conflicted feelings about leaving patients locked up all week while she went about her business in the outside world. She tells other stories of how she exceeded her duties to make sure a patient remained safe from him or her self. I was confused about her references to her attraction to other doctors and her brazen efforts to have sex with male doctors at the hospital.

But what drew me in were the intense stories she tells of other people's madness. Stories of people who lose grasp of reality due to severe circumstances or childhood abuse are disheartening and frightening. We don't know what will put us over the edge and, possibly, into the hospital. On this subject, Holland writes,

“There is a diaphanous membrane between sane and insane. It is the flimsiest of barriers, and because any one of us can break through at any given time, it scares all of us. We all lie somewhere on the spectrum, and our position can shift gradually or suddenly. There is no predicting which of us will be afflicted with dementia or schizophrenia, who will become incapacitated with depression or panic attacks, or become suicidal, manic, or addicted. None of these states of mind are uncommon, and all of us have friends and family who are suffering with some degree of psychiatric illness. ”

Despite a few reservations, I truly applaud Dr. Holland for sharing her personal journey, as well as the experiences of so many psychiatric patients, with the world. By revealing all these stories, she helps to diminish the stigma that some people feel for having or seeking treatment for mental illness.