10 Months (and a few days) of Motherhood

/I passed my books to the clerk at the library, who then handed them back to me, saying, “Your due date is August 22nd.” I wanted to tell him, “No, my due date is and always will be September 29.” The phrase due date is forever imprinted in my mind in relation to the birth of my child, the most monumental shift in my identity and existence.

One of the books I chose today is called The Fifth Trimester: The Working Mom’s Guide to Style, Sanity, and Big Success After Baby. I’d noticed it before in bookstores and passed on it, my own "fifth trimester" come and gone, but seeing it now, at the library, I reached for it to take it home for free. While I’m usually leery of books that make such lofty promises, I figured there was nothing to lose by checking it out. With a cover checkered with check boxes of to-do list items, it seems relevant, painfully so.

It pains me, too, that this is a women’s problem--managing life after baby, that is. There are fatherhood books, but most are hyperbolically comic, the joke being that dads are helpless when it comes to babies. (Of course, this is patently false.) But I feel helpless when it comes to babies! I’ve figured a lot of things out by necessity: how to pack a diaper bag, how many extra sets of clothes to pack in a diaper bag, how to make funny faces and sounds to entertain the baby during a pungent diaper change, how long to bake zucchini until it becomes soft enough to be consumed with only the stubs of two teeth, how to read the fine print on nursing pads, how to weigh the merits of various baby gear sites in order to purchase the least frustrating option in a given genre of baby paraphernalia, how to cut a band aid in half length-wise and adhere it to the baby mid-squirm.

The mental load, the all-consuming nature of motherhood, the endless to-do list: no matter how it is configured, whether as sociological phenomenon, physiological or emotion reaction, or task-oriented approach, motherhood overwhelms all else, most of the time. And when it doesn’t, when I neglect to order guacamole in addition to our burritos simply because the baby likes it, I feel guilty.

I do not forget her tears. An hour or so after she falls asleep at night, I turn to my phone to re-watch a video of her from earlier in the day. I agonize over whether to keep a band-aid on her finger while she sleeps. I worry that she is too cool, too hot, too sandy, too sticky. Do I read her too many feminist empowerment books, so many that she’ll wonder why I keep insisting that she can be whatever she wants to be and do whatever she wants to do?

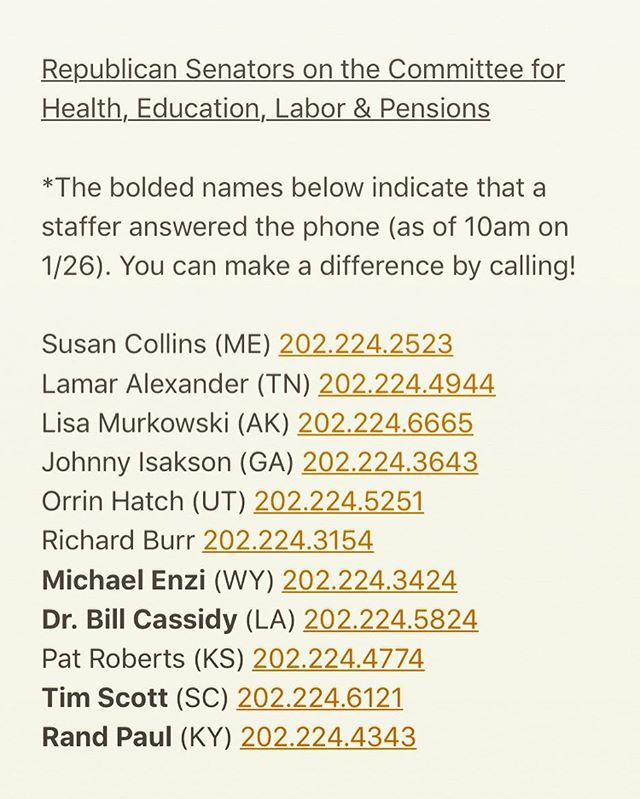

Last year, when I was pregnant, I promised myself that my writing would not become all about motherhood or babies, as though there were something inherently wrong with that. My impulse is to write about what I know, and how I see the world, and with a child now, all of that has changed. From uncovered outlets and sharp coffee table edges, to healthcare policy and the gender pay gap, I am concerned for her, and I see all of these obstacles with her in mind.

So when I happened upon Sarah Menkedick’s new book, Homing Instincts, I felt relief and validation: writing about motherhood is, indeed, real writing. The tedious parts of motherhood don’t render the experience simple. There is complexity and nuance in the experience of raising and caring for a human being. And just as I hope we all respect mothers out in the world (those who are feeding their babies, or toting them on planes or buses, or merely trying to buy groceries) because we were all babies once, and we all needed our mothers, I would hope that we can all see the richness in delving into the complexity of becoming and being a mother.

Menkedick's op-ed in the LA Times just prior to the book's release captures this tension:

I am standing before a small audience in Columbus, Ohio, apologizing for what I’m going to read. “It’s about motherhood,” I say, then quickly qualify, “but you know, more than that! It’s about stories, and self, and the meaning of home.” I have been doing this for months, explaining the book I’ve written as something along the lines of “about motherhood but not really,” until finally, in front of this audience, the absurdity of my intellectual scrambling strikes me. What male writer feels the need to atone for essays about, say, war? I imagine him hurrying to clarify: “But really they’re about the human struggle, triumph over adversity, and the meaning of self.”

As I carry on as a mother to my precious little person, and as I read and write about this experience, I feel the tiniest bit more reassured, thanks to her, in the daily struggle and worry and delight that encompass what motherhood is to me.