My #MeToo

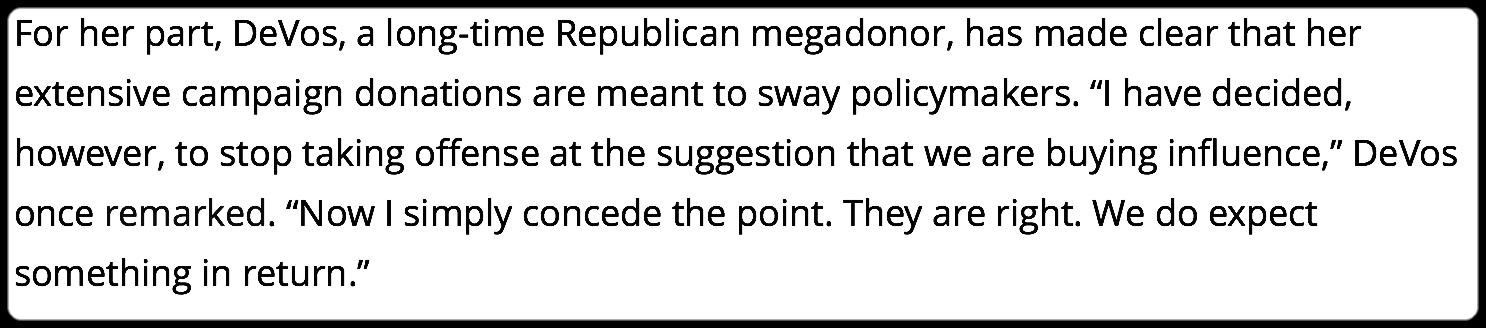

/There are a million terrible things happening. Nothing happening about gun regulations in the five years since first-graders were murdered at school one year ago today. Losing the neutrality of the internet. I could go on, but I think we all know about most of the injustices happening, though maybe not so much about prison gerrymandering or children with disabilities losing their protections in school or voter suppression of minorities.

I don’t think I have anything particularly unique to contribute about most of these issues, but I do think I have something to say about the sexual harassment reckoning. So here it is:

On the biggest day of the #MeToo movement, I wondered why I didn’t have a moment to share. I cringed at the self-exposure, and didn’t want to participate. I didn’t want to say that I had been hurt, because I wasn’t sure if I had been. I haven't had to deal with a hostile work environment, and I wasn't systematically victimized. In other words, I wasn’t sure if I had a #MeToo moment.

But maybe I didn’t have a #MeToo moment because I hadn’t pursued a career in a male-dominated field? Or because I hadn’t spent much time out late in sketchy bars? Had I somehow avoided all this because of inadvertent choices I made? Or maybe I just got lucky?

Or what if I did have a moment? Maybe I did, but did it really count?

That’s how rampant this is: We—women, mostly—lose the ability to discern what counts. But that question itself is suspect. If we question at all if it counts—and we question, of course, because those moments make us question ourselves—then it counts. Of course it counts, I as can see now.

The male administrator condescending to me counts.

The male student telling me to suck his you-know-what counts.

The bad date who spooked me counts.

The guy who followed me home from the bus stop counts.

The father of a male student trying to embarrass me in front of other parents counts.

I used to think it was me they were insulting. I understand now that it was women more generally. These moments weren't about my worthiness, and in fact had nothing to do with me. Each moment was about each man's desire for superiority.

What I experienced wasn’t assault, and maybe doesn’t even constitute harassment. But it was still men wielding sexual power. And that’s never OK.

Almost every day now, as new allegations emerge, I see men and women alike state: “I believe her.” Or, “I believe the women.” These need to stop. What these statements imply is that the credibility of the woman is not enough, that her account must be verified, as if it’s a credit card with a security code. When a woman musters the courage and finds the right circumstances to come forward, we need to believe her. We don’t need to say we believe her, we just need to do it.

This moment has made me feel more rage about gender inequality. It’s not only a problem that individual women are and were being traumatized, it’s a problem that too many women to count have abandoned or foregone entirely careers that they could have excelled in, and it's a problem that we have lost all their potential contributions to society.

And on top of that, how can these people—who clearly don’t see women as equals—make laws or interpret the laws? I just can’t handle it. So I’m angry now in a way that I wasn’t at the time these things happened to me because I had simply been conditioned to think that this was how things were.

I truly didn't understand the extent of this problem. I didn't understand how much we still need feminism. I didn't understand how I might have been subtly directed toward a career that was lower in pay and status simply because it has been traditionally female. I didn't understand how pervasive and insidious this—harassment, assault, sexism, misogyny—still is.

#Enough