Meandering in Boston

/This weekend, as part of my current and somewhat accidental career meandering phase, I’m in Boston for the International Literacy Association (ILA) annual convention. The past couple months, I’ve been toying with the idea of returning to school to learn more about reading, literacy, and curriculum development. But before I do, I wanted to see if it was going to be the right fit. I’m taking an online class (called "Word Study”) to learn more about spelling and reading development, and I’m here, attending this conference, to see if the field excites me. We shall see …

Just to be clear, I don’t particularly enjoy working part-time. I like doing something useful and feeling competent in return. Though I appreciate having the flexibility to exercise in the middle of the day, go grocery shopping when the store isn't crowded, and the like, I do miss colleagues and a regular schedule. Since March, my work with students has required about ten to fifteen hours a week, which includes prep time, time with students, driving to meet students, and emailing parents. Yet reading for pleasure—either novels absorbing enough to distract me from the miseries of the third trimester or parenting books to feed my obsession—doesn’t confer the same sense of competence and fulfillment as working with kids.

I would have liked graduate school to work out; once it became clear that it wasn’t going to, I would have liked to get back to full-time work. Only, that wasn’t realistic, given the persistent vomiting that struck around week 5 of pregnancy and continued, with only mild abatement, to the present, at almost 29 weeks. For instance, just two days ago, I started puking while driving—one hand on the steering wheel, the other holding open the doggie poop bag I was lucky enough to have in the front seat with me.

Anyway, the conference has been useful, albeit unsurprisingly overwhelming, thus far. Yesterday I attended a session about effective word study instruction with Kathy Ganske, a professor of literacy at Vanderbilt. I also went to very disorganized session on teaching nonfiction and a less than useful session on the logistics of implementing a summer reading remediation program. There are few things that puzzle me more than teachers and professors of literacy not knowing how to present information! But, barring a few other annoyances—the most egregious being people taking photos of every single slide in a presentation—I’ve been learning about the literacy field and feeling excited and invigorated about working in a school again.

When I showed up for a session on phonics at 8 am (quite a feat in my current state), I found the presenter not present! I quickly looked on the conference app for another session to attend and luckily found one nearby about recent findings in dyslexia research. The researchers dispelled some points of contention regarding dyslexia among educators, including:

- The idea that dyslexics have special talents in art, music, or related disciplines. There is no research that indicates that dyslexics are any more likely to excel in these areas than anyone else.

- That 15-20% of the population is dyslexic. Although diagnostic criteria vary widely among districts, states, and countries, the actual percentage of the population that is truly dyslexic is closer to 1-2%.

- Finally, the claim that dyslexics require an explicit, systematic, multi-sensory program in order to learn to read. There is no evidence for this. In fact, evidence supports the idea that early intervention, especially phonological instruction, is more effective at reducing the number of children at risk for reading difficulties.

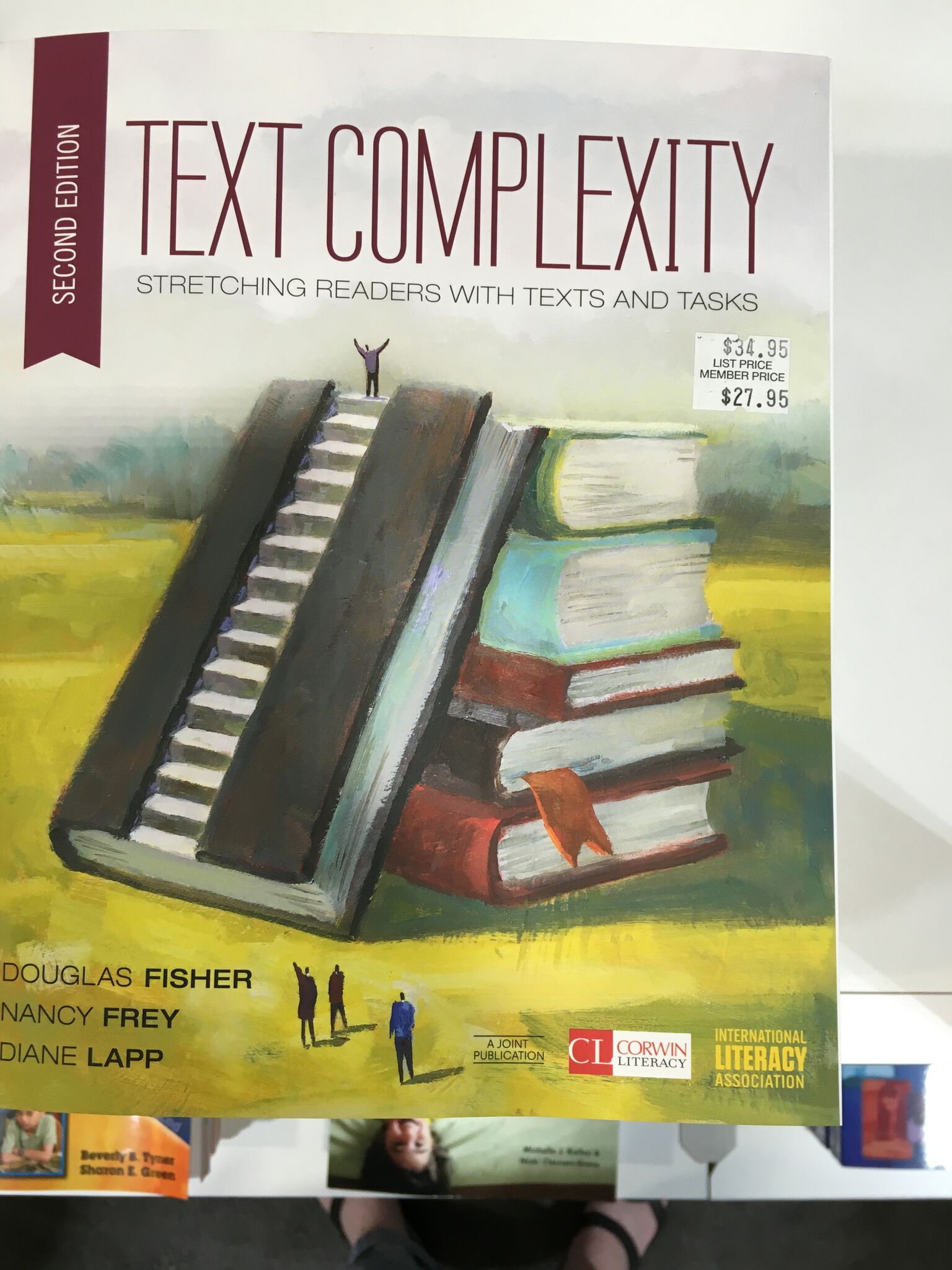

Yet my favorite part of the conference was the two sessions I attended earlier today with Doug Fisher and Nancy Frey. In the first, they talked about lessons they have learned relating to adolescent literacy. In the second, they discussed how to apply John Hattie’s findings about visible learning to literacy teaching. Overall, here are the key points:

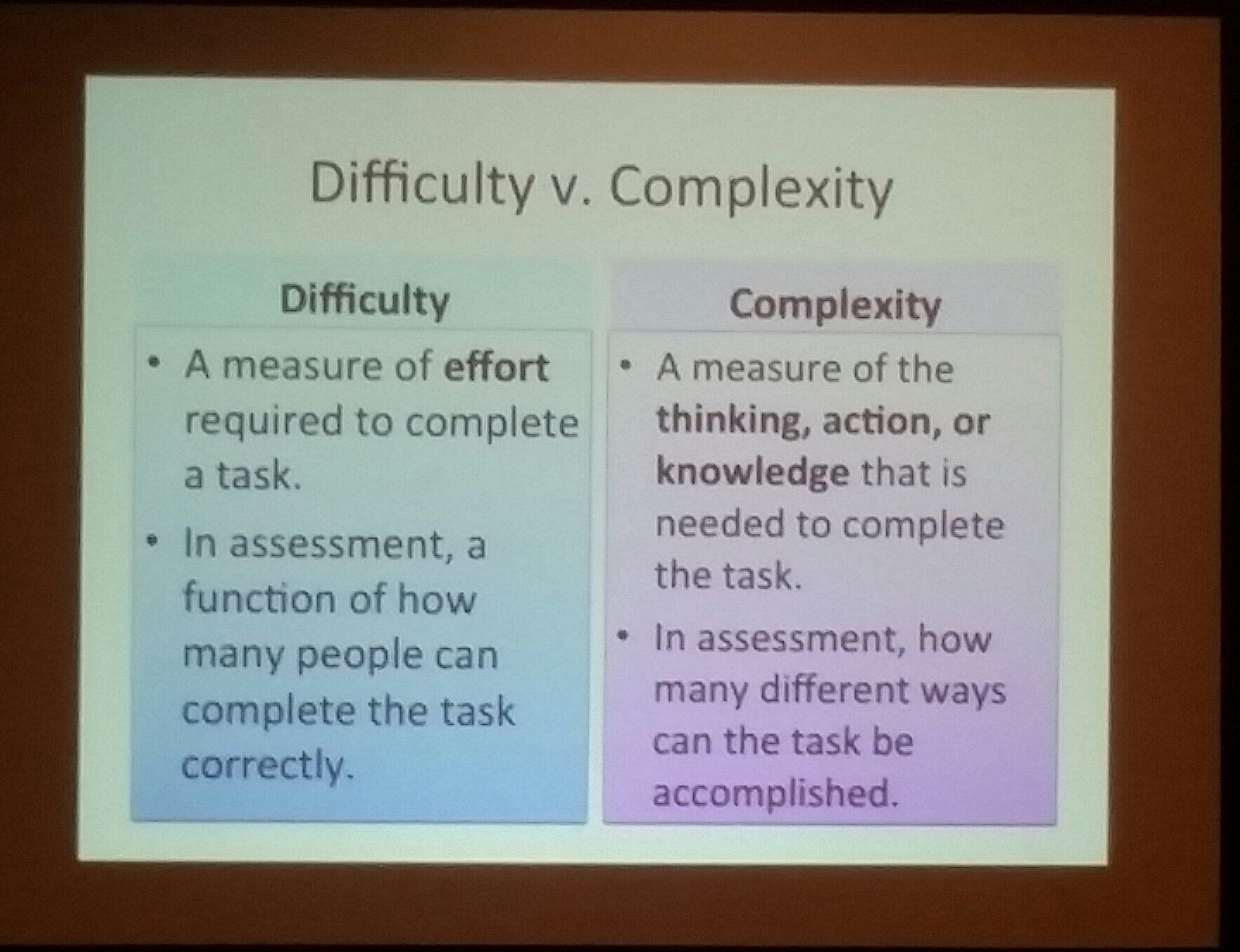

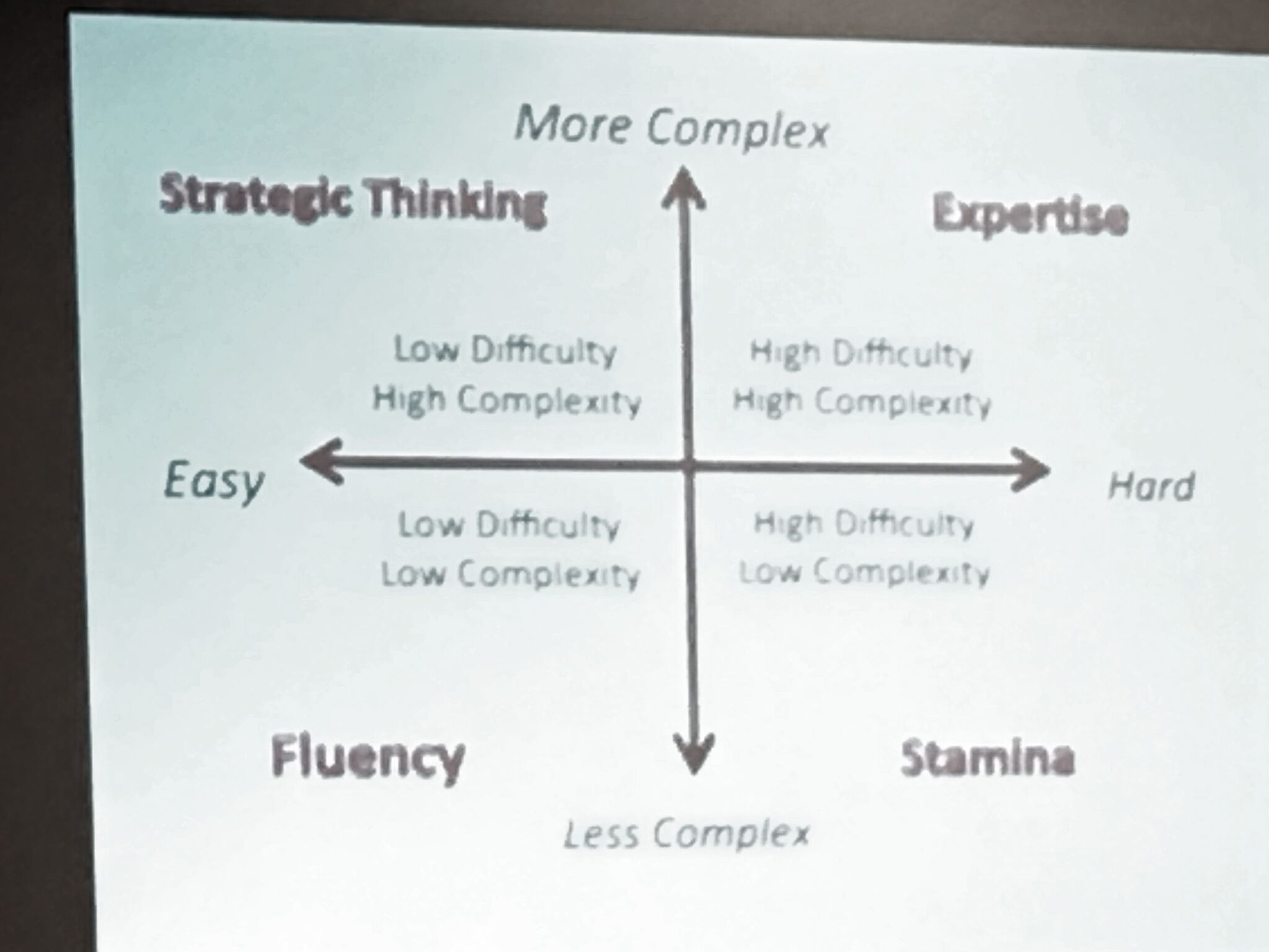

Challenging expectations and standards are appropriate. Kids should know that school is supposed to require hard work and effort—it’s not meant to be easy! Fisher and Frey discussed the concept of “rigor” (often a buzzword meaning nothing) and how they came to the conclusion that it is a balance between difficulty and complexity. They define difficulty as the measure of effort required to complete a task and complexity as the number of ways and methods of thinking, action, or knowledge needed to complete a task. They plan to have teachers at their school organize their syllabus and assignments using the following model:

Student comprehension and collaboration are crucial.

In their revised take on speaking and listening standards--in which they call for students to build on each other's ideas and express their own clearly and persuasively--they advocate for and actually require at their school that 50% of instructional minutes are spent in collaborative learning. Their research shows that doing so increases student satisfaction and therefor attendance, motivation, engagement, etc. They cited a study by John Hattie in which he looked at 3,000 matched pair classrooms. In low-achieving classrooms, teachers talked 89% of the time, whereas in high-achieving classrooms, teachers talked only 49% of the time.

“Every student deserves a great teacher, not by chance, but by design.”

There are definitely ways to make this happen! Part of the problem, in my opinion at least, is that not enough people with decision-making powers are aware of the research and are willing to make changes based on it. According to John Hattie’s research, an effect size of .4 represents about one year of growth; therefore, practices that produce less than .4 of an effect size mean that students do not progress adequately, whereas policies that create larger effect sizes produce more than a year of change in one year. Here are the effect sizes for common practices:

- grade-level retention: -1.3 effect size

- ability/group tracking: .12 effect size

- teaching test-taking: .22 effect size

- homework: .29 effect size (though homework at the secondary level has a stronger effect than it does at the elementary level)

- small-group learning: .49 effect size

- teaching study skills: .59 effect

- repeated reading to build comprehension: .67 effect size

- classroom discussion: .82 effect size (about 2 years of growth for one year of school!)

- collective teacher efficacy: 1.57 effect size (for example: PLCs, grade-level teams)

The final session I attended today was a panel about strategies for teaching nonfiction featuring literacy stars Penny Kittle, Kylene Beers, and Bob Probst. They recommended some nonfiction books, and I look forward to checking these out:

- How: Why How We Do Anything Means Everything - Dov Siedman

- Collaborative Intelligence - Dawna Markova & Angie Mcarthur

- Minds Made for Stories - Tom Newkirk

- A History of Reading - Albuerto Manguel

- Far From The Tree - Andrew Solomon (Quite a tome, yet a fantastic, compelling read!)

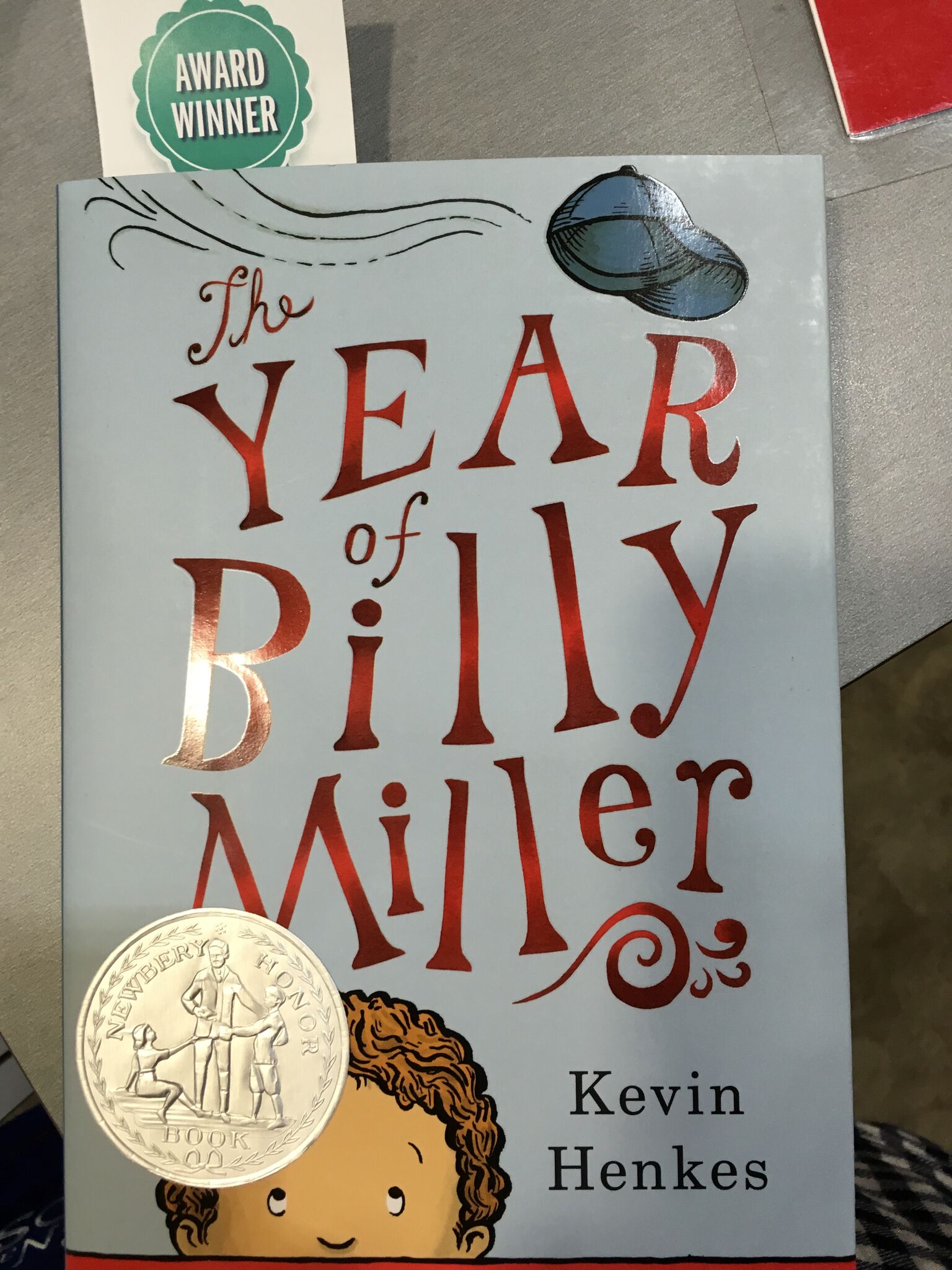

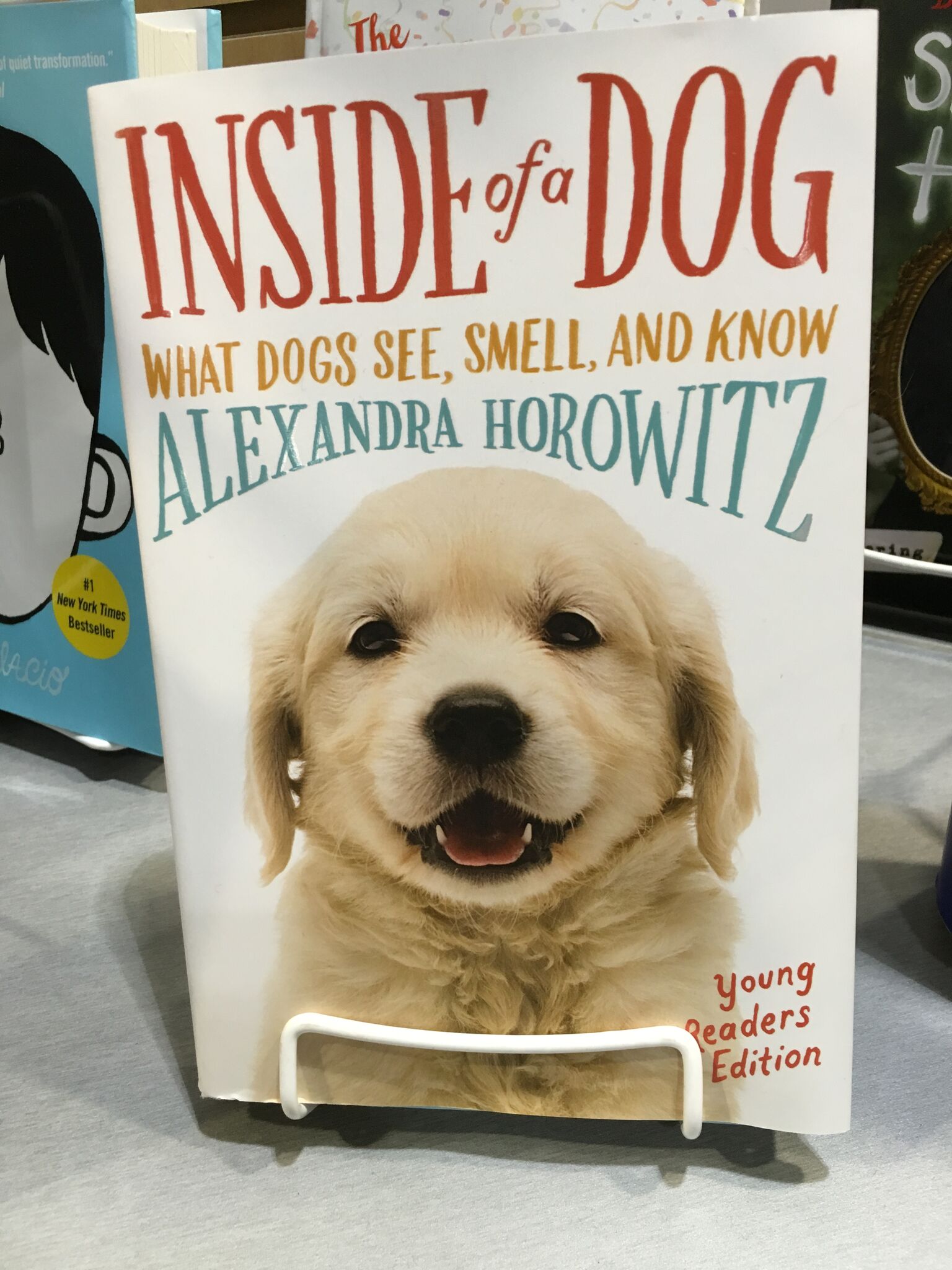

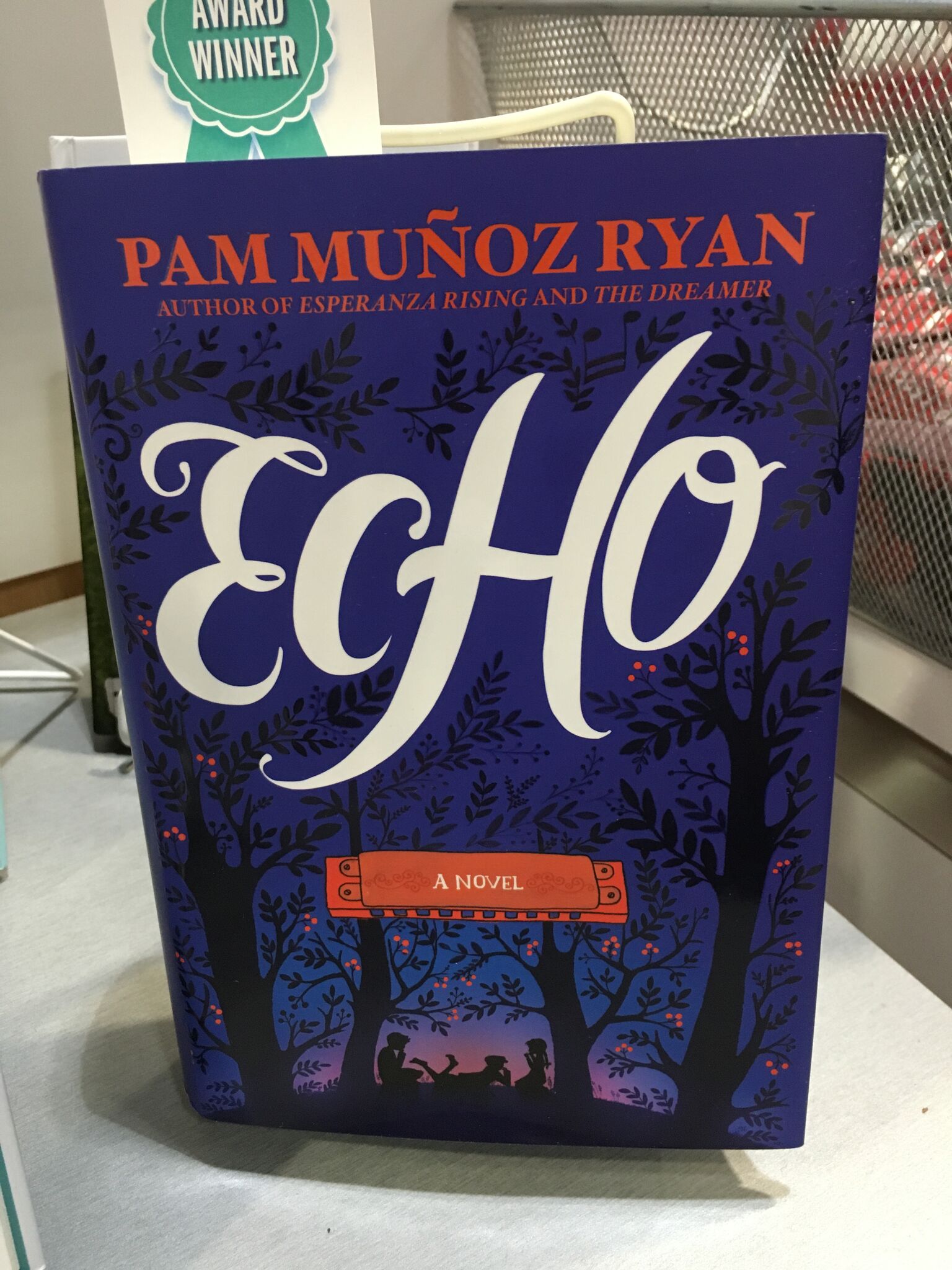

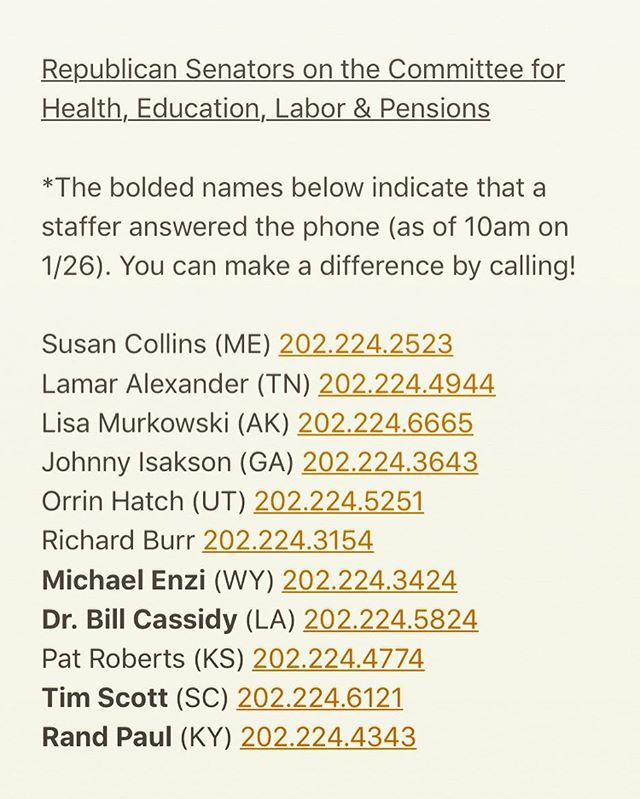

Finally, here are some books I *may* have purchased, am curious about, would like to read, or may recommend to students. Enjoy!